The Not Firsts

“Black Opera and Black Classical music did not begin with Scott Joplin. Awareness of this music on a wide, societal scale, however, is a recent phenomenon. So is inclusion of this music in historically White concert halls and theatres. So when speaking of “firsts” in the 21st century, it’s important to ask: “Why are these firsts? What has actually been going on all these years?”

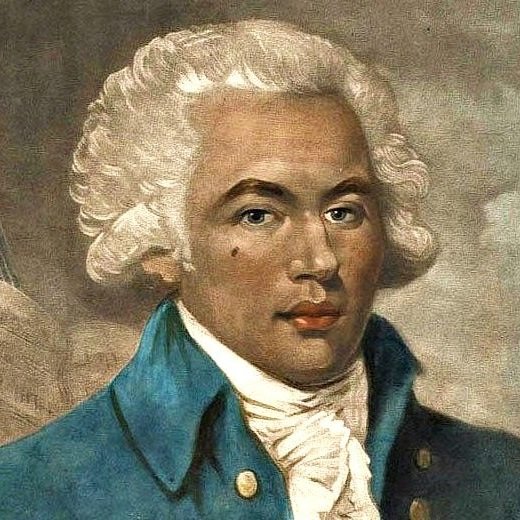

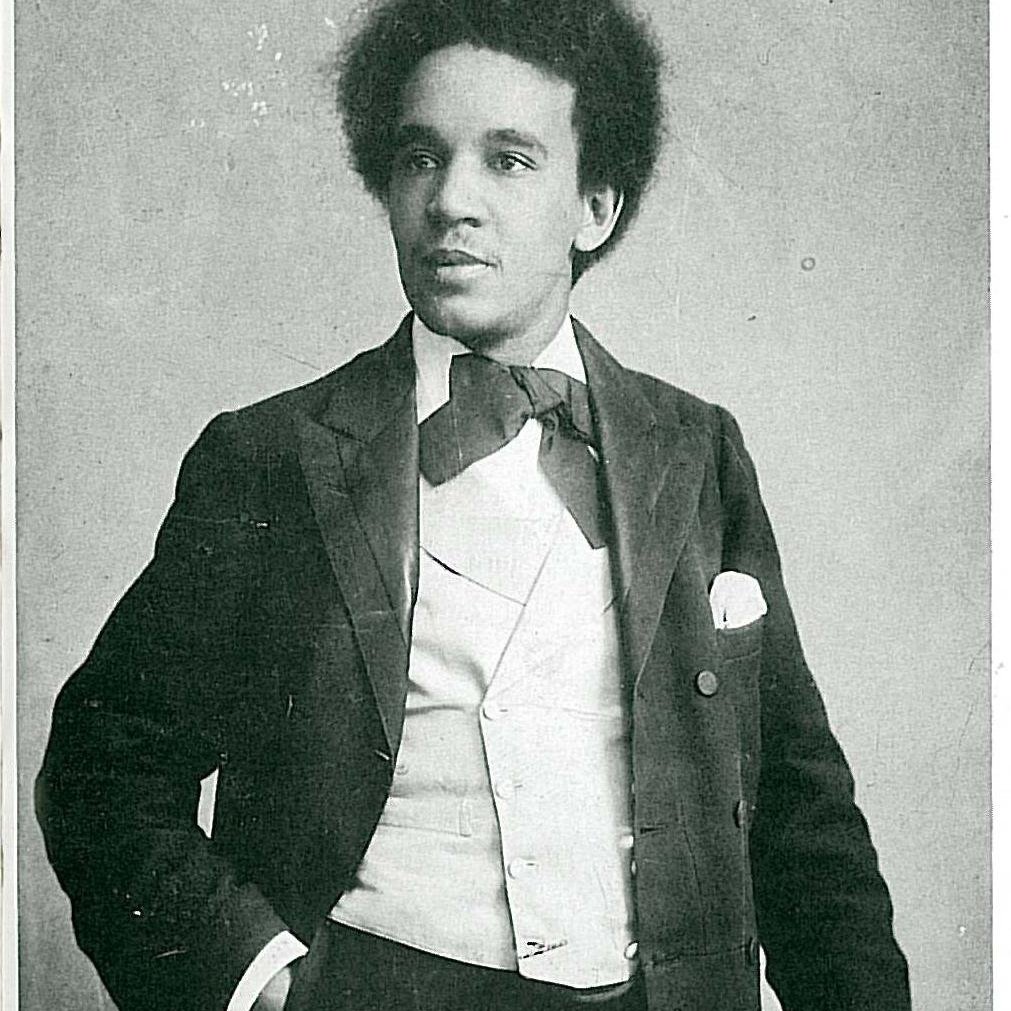

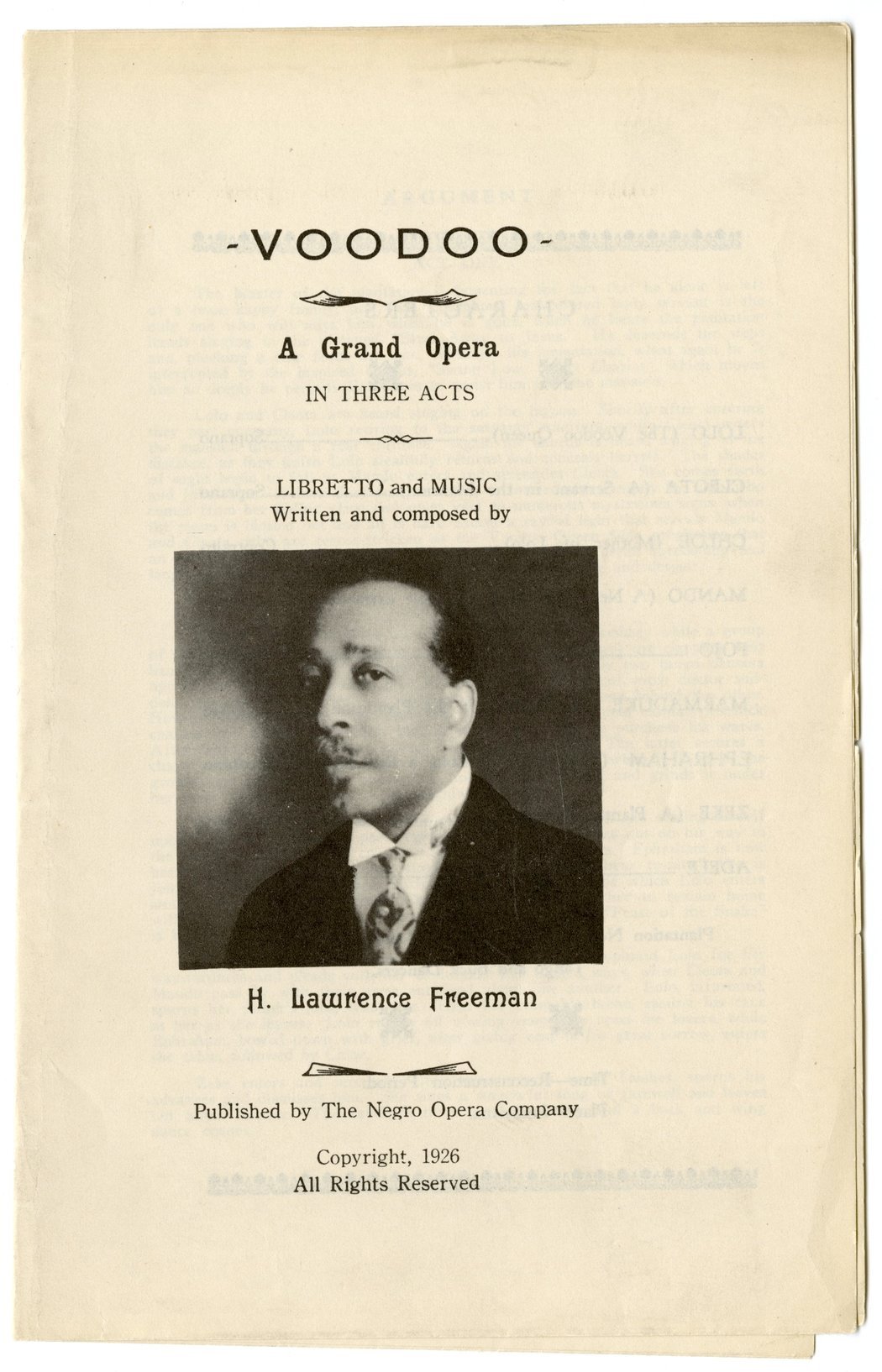

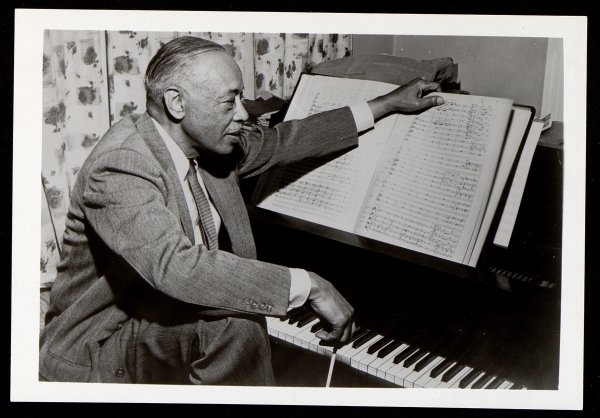

Black American composers were working on operas (often comic or ragtime operas) throughout the late 1800s. Many of these compositions are now lost (perhaps erased or discarded might be better verbs?). Harry Lawrence Freeman is the first African American to write an opera that managed to make it to the present day (access to the means of preservation was not remotely equitable in the late 1800s, as the cost of printing full scores was exorbitant and skewed heavily towards White composers backed by White publishers). Freeman’s The Martyr premiered in 1893. In 1900, decades before the desegregation of mainstream opera houses, the African American baritone Theodore Drury founded an opera company that presented – to enormous acclaim – operas from the standard repertoire performed by largely African American casts. Joplin’s own two operas were written in the late 1800s (A Guest of Honor – a now “lost” ragtime opera) and in the early 1900s (Treemonisha – Joplin’s only “grand” or serious opera – partially “lost”. A further loss, in fact, is that Joplin worked on revising Treemonisha with Harry Lawrence Freeman, after it was published – the two men being in the same circle in New York at the time. Those revisions, too, did not survive). Meanwhile, in Europe, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor had become famous from his base in London in the late 1800s, and, even further back, Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saints-Georges, and George Bridgetower were both composing in the European classical tradition in the late 1700s.

Could Black Classical be considered its own genre, with its own set of distinct ingredients? That’s a question with no singular answer. But, certainly, Black musicians have been intersecting with European Classical traditions on their own terms for centuries. Often the music they have created has resulted from, even thrived on the collision of European Classical music with the many musical worlds that African diasporic people occupy worldwide. This Black Classical tradition can claim a great many composers over a great many generations – from Bologne in the 1700s, to Freeman and Joplin and Harry T. Burleigh in the early 1900s, to Canadian-born Nathaniel Dett through the 1920s and beyond, to Shirley Graham Du Bois (perhaps the first Black woman to have an opera performed, in 1932), to Florence Price (the first Black woman composer performed by a major symphony orchestra, in 1933), all the way past William Grant Still, Duke Ellington and Nina Simone to our own Jessie Montgomery and kora virtuoso, Tunde Jegede. The names are legion – far too many to write here. Even more have suffered erasure from “official” history. Yet – recorded or not, remembered or not – all have brought their own voices to this musical form. It is an old and storied tradition, with many threads and variations. It is music that is neither entirely European, nor entirely pop, nor folk, nor gospel, nor blues, but has an energy and classicism of its own.

It is also not new. If there are still “firsts” happening, the reasons for this have nothing to do with the folks who have been writing the music for the past couple of centuries.

On Sept. 19, 2019, the New York Times (finally) concurred by publishing this: “That “Porgy and Bess” — written by three white men, the Gershwin brothers and DuBose Heyward — has become known as the quintessential opera of the Black American experience is a symbol of both the systemic racism found throughout the arts and the specifically slow-to-modernize nature of the operatic canon.”